Sacrifice

They hearkened to the call and thus

They found themselves amidst a rush

Of bursting shrapnel and of shell

A veritable roaring Hell

Then fell that Liberty might live

Heroes who did sincerely give

All that they loved and lived to call

Mother, Sister, Sweetheart, Wife all

And dying what a sacrifice!

Two deaths in one and dying twice

Killed down the iron crown of might

Giving to each man a freeman’s right

They who into their graves were thrust

Still live – their tombs can hold but dust

– Joseph P. O’Shea, 1921

Dr. Joseph Patrick O’Shea, was my husband Doc’s father. He was a medical doctor, and became a Captain in the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps during World War I. He also wrote poems and prose, like his friend and fellow countryman John McCrae most famously did in the writing of In Flander’s Fields. This poem, Sacrifice, is one amongst dozens upon dozens of poems in just one of his notebooks that I’ve managed to keep, nearly a century old.

The paper and pen was often their only outlet to keep them going. I’ve heard that while the doctors were busy amputating a limb, blood saturating the floor all around them and amidst screams of agony, they would be composing poetry in their heads, trying hard not to focus on the horrific act they were undertaking. And obviously, as seen by this poem, the great sacrifices that had been made and the memories the soldier-doctor had of war didn’t stop running through his mind just because the Great War had ended.

Dr. Joe (as he was affectionately called) volunteered for service. He was 37 when he signed up, five years out of medical school at the University of Laval in Quebec City in 1912. After graduating, Joe moved out to Saskatchewan, as did another physician he’d gone to school with; Joe set up practice in Radville and his friend, Dr. Parent, in Sedley.

I would be remiss not to tell you more of Joe’s life, or to write down what I remember, since there is really no one left to tell. Though Joe had an Irish name, he was born in Scotland. When his parents died, he was sent as a youngster to the USA to live with his aunt in Vermont. But she, too, died young and the boy, now an orphan, was sent to an orphanage run by Jesuits.

When Joe finished high school, the priests told him to go north, to Quebec, where he could find work on the railroad and make enough money to afford tuition. He’d be able to study in Quebec City, but although Quebec was French, they were sure he would be able to master it quickly, especially after working on the railroad. And Quebec City was a Jesuit town: the Jesuits there could help get him into the school, but the hard work would be up to him.

It took Joe eleven years before he graduated. His Catholic upbringing and humble past was a continual influence throughout his life: he and his wife Bridgetta Connaughty, who he married in 1922, adopted Doc when he was just two years old, but that is a story for another day.

I want to re-post something I found on the horrors of World War One. If we hadn’t made the sacrifices in World War I and World War II, we would not have the freedom we cherish so much.

Canada Goes to War

In 1914, Canada was considered a part of the British Empire. This meant that once Britain declared war, Canada also was automatically at war. The First World War opened with great enthusiasm and patriotism on the part of Canadians, with tens of thousands rushing to join the military in the first months of the conflict so they would not miss the action. They need not have worried. The war would grind on for more than four years, killing more than ten million people in fighting that would be revolutionized by high-explosive shells, powerful machine guns, poison gas, submarines and war planes.

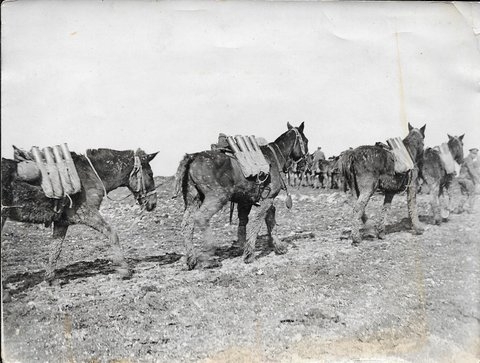

Dr. Joe was poisoned by the mustard gas in the Belgian town of Ypres. As bombs were shelling around them for two days straight, Dr. Joe and his medical team took shelter in the basement of a hotel and continued to attend to the wounded. He was later transferred to a Army base in India to recuperate until he came back to Canada.

These are some of the conditions these doctors worked under during that war. Here is an excerpt from The Battalion Doctor

It is the cold and nervous hour before the attack. The Medical Officer is in a position immediately behind the “jumping off” line. He has organized his staff to cover the battalion front and with his sergeant and corporal burdened with medical supplies, he waits the barrage. As soon as it falls he moves off with the first wave of attack. For him it is not a question of waiting in a dugout to receive the wounded, he must be with the battalion to do the ordinary work of first aid and to establish his dressing station the moment the “objective” is reached. So he goes into the smoke and tumult of action, to take his chance and, if need be, to give his life to the service of his men.

How many owed their lives to him

No man shall tell;

over the top in half-light din,

Into the fiery hell,

Unsent he went,

Seeking them there,

And to the depths of their despair

Came like an answered prayer.

The M.O. (medical officer) in action was beloved of every man who saw him in action. An aid post is a grim spectacle. There are rows of stretchers, huddled groups of walking canes, blood everywhere and the sound of suffering in the air but in the midst the doctor at his merciful work, haggard and wan he may be from sleepless nights an unresting days, but he has about him an air of authority, a suggestion of undismayed confidence which, in itself, reassures and comforts weary men. Honour to which honour is due! Be he the battalion doctor or the officer in the field ambulance, or the surgeon in the operating room of the casualty clearing station, or the base hospital, here is a man who through courage and devotion has maintained and advanced the traditions of a professional which from its earliest days, has stood for unselfish service of mankind.

Hi, I’m Erik’s cousin and I would like to congratulate you on your wonderful and interesting, heartfelt posts. I thoroughly enjoy reading them and it is such an amazing legacy you are leaving your children and grandchildren. I’m sure there are many old and new friends that look forward to each and every one with anticipation. Thank you for a lovely read! Sincerely, Sandy

Thank you so much Sandy. It has been a big challenge to learn so much but also very rewarding. I have even been amazed at what I can remember. The IPad is such a good camera and my skills have improved with the picture taking.