Medical Care WW1 and Fellow Canadians who served in WW1 in France

Medical Care WWI

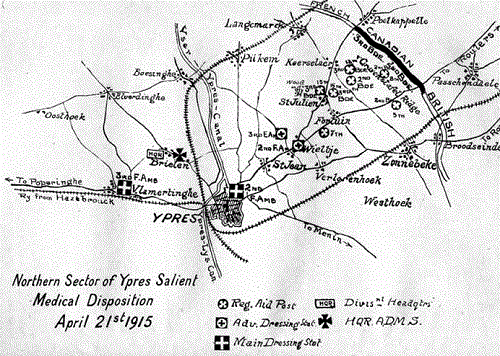

This diagram from Canadian history shows the locations and types of aid posts and dressing stations that supported the 1st Canadian Division during the opening of the Second Battle of Ypres. There are six regimental aid posts behind the front line, two Advanced and two Main Dressing Stations.

Aid and Bearer Relay Posts

The casualty is likely to have received first medical attention at aid posts situated in or close behind the front-line position. Units in the trenches provided such posts and generally had a Medical Officer, orderlies and men trained as stretcher bearers who would provide this support. The Field Ambulance (see below) would provide relays of stretcher bearers and men skilled in first aid, at a series of “bearer posts” along the route of evacuation from the trenches. All involved were well within the zone where they could be under fire.

Field Ambulance

This was a mobile medical unit, not a vehicle. Each British division had three such units, as well as a specialist medical sanitary unit. The Field Ambulances provided the bearer posts but also established Main and Advanced (that is, forward) Dressing Stations where a casualty could receive further treatment and be got into a condition where he could be evacuated to a Casualty Clearing Station. Men who were ill or injured would also be sent to the Dressing Stations and in many cases returned to their unit after first aid or some primary care.

This was a mobile medical unit, not a vehicle. Each British division had three such units, as well as a specialist medical sanitary unit. The Field Ambulances provided the bearer posts but also established Main and Advanced (that is, forward) Dressing Stations where a casualty could receive further treatment and be got into a condition where he could be evacuated to a Casualty Clearing Station. Men who were ill or injured would also be sent to the Dressing Stations and in many cases returned to their unit after first aid or some primary care.

Dressing Station

An Australian Medical Officer attends a wounded man at an Advanced Dressing Station during the Third Battle of Ypres in 1917. Imperial War Museum copyright image E(AUS)714.

There was no hard and fast rule regarding the location of a Dressing Station: existing buildings and underground dug-outs and bunkers were most common, simply because they afforded some protection from enemy shell fire and aerial attack. The Dressing Stations were generally manned by the Field Ambulances of the Royal Army Medical Corps.

Once treated at a Dressing Station, casualties would be moved rearward several miles to the Casualty Clearing Station. This might be on foot; or on a horse drawn wagon or motor ambulance or lorry; or in some cases by light railway. It is helpful to consult the war diary of the Assistant Director of Medical Services of the Division relevant to the man’s unit, for they usually have very detailed reports on the locations of the bearer and dressing stations at the time that the man was being evacuated.

A Field Ambulance wagon passing over muddy ground near Ovillers, Somme, in September 1916. Imperial War Museum copyright image Q1098. This may be on its way from a Dressing Station to a Casualty Clearing Station. Imagine what wounded men suffered when moving over such ground on this type of transport.

Casualty Clearing StationThe CCS was the first large, well-equipped and static medical facility that the wounded man would visit. Its role was to retain all serious cases that were unfit for further travel; to treat and return slight cases to their unit; and evacuate all others to Base Hospitals. It was often a tented camp, although when possible the accommodation would be in huts. CCS’s were often grouped into clusters of two or three in a small area, usually a few miles behind the lines and on a railway line. A typical CCS could hold 1,000 casualties at any time, and each would admit 15-300 cases, in rotation. At peak times of battle, even the CCS’s were overflowing. Serious operations such as limb amputations were carried out here. Some CCS’s were specialist unit, for nervous disorders, skin diseases, infectious diseases, certain types of wounds, etc. CCS’s did not move location very often, and the transport infrastructure of railways usually dictated their location. Most evacuated casualties came away from the CCS by rail, although motor ambulances and canal barges also carried casualties to Base Hospitals, or directly to a port of embarkation if the man had been identified as a “Blighty” case. (In 1916, 734,000 wounded men were evacuated from CCS’s by train and another 17,000 by barge, on the Western Front alone. There were 4 ambulance trains in 1914 and 28 by July 1916). The serious nature of many wounds defied the medical facilities and skills of a CCS, and many CCS positions are today marked by large military cemeteries. CCS’s also catered for sick men. Generally, considering the conditions, the troops were kept in good health. Great care was taken in reporting sickness and infection, and early preventive measures were taken. The largest percentage of sick men were venereal disease cases at 18.1 per 1000 casualties; trench foot was next with 12.7. Until mid-1915, the CCS was known as a Clearing Hospital. Generally, there was one provided for each Division. From the CCS, the casualty would be evacuated to a Base Hospital.

Ambulance Trains and Barges

Casualties would normally be moved from the CCS to a Base Hospital, by specially-fitted ambulance train or in some circumstances by barge along a canal.

Base Hospital

Once admitted to a Base Hospital, the soldier stood a reasonable chance of survival. More than half were evacuated from a General or Stationary Hospital for further treatment or convalescence in the United Kingdom. The Stationary Hospitals, two per Division, could hold 400 casualties each. The General Hospital could hold 1040 patients. They were located near the army’s principal bases at Boulogne, Le Havre, Rouen, Le Touquet and Etaples. The establishment of a General Hospital included 32 Medical Officers of the RAMC, 3 Chaplains, 73 female Nurses and 206 RAMC troops acting as orderlies, etc. The hospitals were enlarged in 1917, to as many as 2,500

A ward of the 2nd Australian Casualty Clearing Station

at Steenwerke, November 1917. Imperial War Museum

copyright image E(AUS)4293.beds.

Home hospital

Existing military hospitals were expanded; many civilian hospitals were turned over in full or part to military use; many auxiliary units opened in large houses or public buildings; and many private hospitals also operated.

Military hospitals established at hutted army camps

Land either on existing army bases or acquired nearby for the purpose was converted into major hospitals.

Red Cross, St John’s Ambulance, auxiliary and private hospitals

Large numbers of public and private buildings (often large houses) were turned over for use as small hospitals, most of which operated as annexes to nearby larger hospitals. These are not listed below.

Specialist hospitals

Some hospitals were developed as, or became, specialist units. Categories of specialism included mental hospitals, units for limbless men, neurological units, orthopaedic units, cardiac units, typhoid units and venereal disease.

Convalescent hospitals

These establishments did not have the usual civilian meaning of convalescence; they were formed from March 1915 onward to keep recovering soldiers under military control. See also the Command Depots

Auxiliary hospitals in the UK during the First World War

At the outbreak of the First World War, the British Red Cross and the Order of St John of Jerusalem combined to form the Joint War Committee. They pooled their resources under the protection of the red cross emblem. As the Red Cross had secured buildings, equipment and staff, the organization was able to set up temporary hospitals as soon as wounded men began to arrive from abroad.

The buildings varied widely, ranging from town halls and schools to large and small privatehouses, both in the country and in cities. The most suitable ones were established as auxiliary hospitals. Auxiliary hospitals were attached to central Military Hospitals, which looked after patients who remained under military control. There were over 3,000 auxiliary hospitals administered by Red Cross county directors.

In many cases, women in the local neighborhood volunteered on a part-time basis. Thehospitals often needed to supplement voluntary work with paid roles, such as cooks. Local medics also volunteered, despite the extra strain that the medical profession was already under at that time. The patients at these hospitals were generally less seriously wounded than at other hospitals and they needed to convalesce. The servicemen preferred the auxiliary hospitals to military hospitals because they were not so strict, they were less crowded and the surroundings were more homely.

Fellow Canadians who served in WW1 in France

Georges Phileas Vanier

Vanier was with the Canadian Corps when, following the failure of the German offensive in the spring of 1918, the Allies took the initiative again and against all expectations won a brilliant victory starting with the first attack east of Amiens on August 8. The succeeding campaign inspired a number of heroic acts leading to the German defeat, but also resulting in crushing losses to all the armies there. Vanier’s battalion, for example, was decimated during the capture of Chérisy at the end of August and during the ensuing counterattacks. Vanier himself, replacing Lieutenant Colonel Dubuc who had been wounded on the first day, was put out of action the following day, and his right leg was later amputated.

Enlisting as an officer in 1914, Georges Philéas Vanier joined the ranks of the 22nd Battalion in 1915. Gradually rising through the ranks, he earned decorations for bravery along the way and even briefly commanded the battalion. After the war, Vanier had a brilliant military and diplomatic career culminating no doubt in his appointment in 1959 as Governor General. The second Canadian and first French Canadian to hold this office, he remained Governor General until his death in 1967.

Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae

Born in Guelph, Ontario, on November 30, 1872, John McCrae was the second son of Lieutenant-Colonel David McCrae and Janet Simpson Eckford McCrae. He had a sister, Geills, and a brother, Tom. The family were Scottish Presbyterians and John McCrae was a man of high principles and strong spiritual values. He has been described as warm and sensitive with a remarkable compassion for both people and animals.

John McCrae began writing poetry while a student at the Guelph Collegiate Institute. As a young boy, he was also interested in the military. He joined the Highfield Cadet Corps at 14 and at 17 enlisted in the Militia field battery commanded by his father. While training as a doctor, he was also perfecting his skills as a poet. At university, he had 16 poems and several short stories published in a variety of magazines, including Saturday Night.

He also continued his connection with the military, becoming a gunner with the Number 2 Battery in Guelph in 1890, Quarter-Master Sergeant in 1891, Second Lieutenant in 1893 and Lieutenant in 1896. At university, he was a member of the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada of which he became company captain.

In 1898, John McCrae received a Bachelor of Medicine degree and the gold medal from the University of Toronto medical school. He worked as resident house officer at Toronto General Hospital from 1898 to 1899. In 1899, he went to Baltimore and interned at the Johns Hopkins Hospital where his brother Thomas had worked as assistant resident since 1895.

Although McCrae worked hard at his university teaching and at his increasingly busy practice, the advantage of working in a university was that he could take time off. He holidayed at various times in England, France and Europe . . . At times he worked his passage to Europe as ship’s surgeon; he enjoyed ships and the sea. These were the compensations of a bachelor’s life. (Prescott, In Flanders Fields: the Story of John McCrae, p. 70)

On August 4, 1914, Britain declared war on Germany. Within three weeks, 45,000 Canadians had rushed to join up. John McCrae was among them. He was appointed brigade-surgeon to the First Brigade of the Canadian Field Artillery with the rank of Major and second-in-command. In April 1915, John McCrae was in the trenches near Ypres, Belgium, in the area traditionally called Flanders. Some of the heaviest fighting of the First World War took place there during that was known as the Second Battle of Ypres.

On April 17th, 1915 John McCrae earned the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. On June 1st, 1915 McCrae left the battlefront and transferred to Number 3 General Hospital at Boulogne where he treated wounded soldiers from the battles of Somme, Vimy Ridge, Arras, and Passchendaele. The hospital was housed in huge tents at Dannes-Cammiers until cold wet weather forced a move to the site of the ruins of the Jesuit College at Boulogne. During the summer of 1917, John McCrae was troubled by severe asthma attacks and occasional bouts of bronchitis. He became very ill in January 1918 and diagnosed his condition as pneumonia. He was moved to Number 14 British General Hospital for Officers where he continued to grow weak. On January 28, after an illness of five days, he died of pneumonia and meningitis.

On January 5, 1918 McCrae became the first Canadian ever to be appointed as Consultant Physician to the British Armies in the Field. Unfortunately, McCrae died before he could he could take up his new position.

The symbolic poppy and John McCrae’s poems are still linked and the voices of those who have died in war continue to be heard each Remembrance Day.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved, and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders Fields.

Frederick Banting

The man who perfected the use of insulin to treat diabetes in humans tried several times to join the army when war broke out in 1914, but was rejected because he had poor eyesight. He was finally accepted in 1915, did his basic training then returned to medical school. When he graduated in 1916, there was a push to get more doctors into the service so he reported to duty the day after graduation. He won the Military Cross for heroism in 1918 at the Battle of Cambrai where he tended wounded men for 16 hours while was he himself was wounded.

Lester B. Pearson

Canada’s 14th prime minister, volunteered as a medical orderly when the First World War began in 1914. He went overseas in 1915 and served as a stretcher bearer with the Canadian Army Medical Corps. He began as a private but rose to become a lieutenant. He served in Egypt and Greece and even spent some time with the Serbian Army. He transferred to the Royal Flying Corps in 1917. Two flying accidents left him injured and he was later hit by a bus in 1918 during a blackout and he was sent back to Canada.

Norman Bethune

Bethune was famous for his roles as a physician with Mao Zedong’s army and with the Republicans during the Spanish Civil War, but he first saw action in 1914 when he left medical school in order to serve as a stretcher bearer with the Canadian Army’s No. 2 Field Ambulance to serve as a stretcher-bearer in France. He was ultimately wounded by shrapnel then sent to England to recuperate. He returned to Canada and finished his medical degree in 1916. He later joined the Royal Navy in 1917 where he served as a Surgeon-Lieutenant at the Chatham Hospital in England

Grey Owl

Archiblad Belaney, more commonly known as Grey Owl, was an early Canadian conservationist who gained fame through several books and speaking tours. He joined the Canadian Overseas Expeditionary Force in 1915 during the First World War. He served with the the 13th (Montreal) Battalion of the Black Watch as a sniper in France. He was wounded on two separate occasions in 1916, the second one being in the foot which later developed gangrene. He spent time recovering in England then later in Canada. He was ultimately discharged with a disability pension in 1917.

A . Y. Jackson

An artist and member of Canada’s famed Group of Seven, A.Y. Jackson joined the Canadian Army’s 60th battalion in 1915. He was wounded at the Battle of Sanctuary Wood in 1916. While in the hospital, Lord Beaverbrook helped him get transferred to the Canadian War Records branch as an artist. During this time he painted several important works depicting events connected to the war. He became an official war artistwith the Canadian War Memorials between 1917 to 1919.

Conn Smythe

The man who built Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto and was one of the Toronto Maple Leaf’s early and long-time owners, served in the artillery during the First World War. Shortly after winning the Ontario Hockey Association championship in 1915, Smythe joined up with eight other teammates. He went overseas in 1916 where his unit served on the Ypres salient. Smythe won the Military Cross for heroism in 1917 when his battery was attacked by Germans. He later transferred to the Royal Flying Corps where he served as an airborne observer. His plane was shot down and he remained a prisoner-of-war until the Armistice.

Gen. Arthur Currie

What Arthur Currie lacked in charisma, he made up for in strategy. He would push for more arms and plenty of lead time and preparation before mounting an attack. Currie led the Canadian Corps to a series of First World War victories including Hill 70 at Vimy Ridge, Arras, Amiens and the Canal du Nord. The general went on to be knighted and receive the Légion d’honneur, France’s highest decoration.

Margaret MacDonald

When the First World War broke out in 1914, Margaret MacDonald became matron-in-chief of the Canadian Army Medical Corps (CAMC) with a major’s rank, becoming the first woman to receive such a designation in the British Empire.It was her job to marshal and train civilian nurses, overseeing 2,845 Canadian nursing sisters by the end of the war. They cared for soldiers beyond the fighting into the 1920s.

Thanks to Sharon for all your contributions to my blog.

Very noteworthy and informative.

Thanks for reading Rita