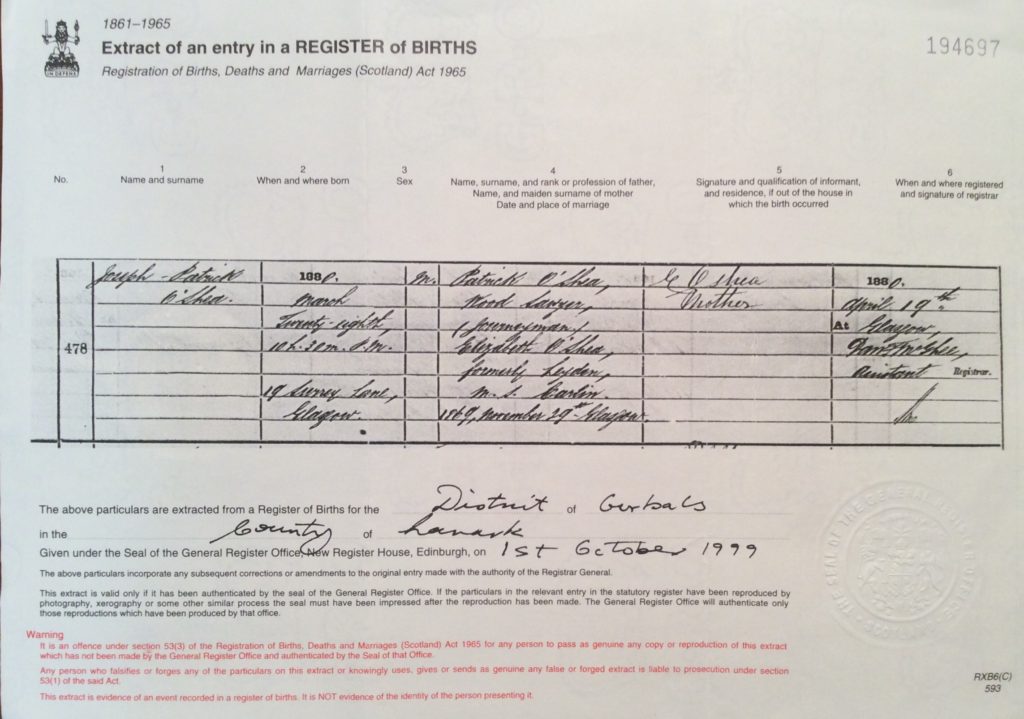

Joseph Patrick O’Shea was born in Glasgow, Scotland at 10:30 p.m. March 28th 1880, the son of Patrick O’Shea, wood sawyer (journeyman) residing at 19 Surrey Lane in the Gerbals District of Glasgow. His mother was Elizabeth O’Shea (formerly Leydon). Joseph’s birth registration includes the marriage date of his parents as November 29th, 1869 and, in addition to his mother’s name as “formerly Leydon”, is “M.S. Carlin”. The M.S. means Maiden Surname. The Gorbals district of Glasgow at that time was a densely populated district on the south bank of the river Clyde. Many who lived there were in worker’s tenement housing.

Other children listed in census records list two sisters, Theresa, born three years earlier (1877), Bridget one year after Joseph (1881) and brother Andrew three years after Joseph (1883). Two other siblings died, each at birth. A sister Helen in 1882 and a brother who was a twin to Theresa in 1877.

Other circumstances of the O’Shea’s family emigration to the United States is not known. One reported entry date is 1890. His father reportedly died “at sea”. Recent knowledge of sister Theresa’s existence in the U.S. indicates at least one known family member was living in the Lewiston Maine area as an adult with whom Joseph may have communicated. It was in Lewiston that Joseph’s formative years were spent. While there he spent some time at an orphanage in Lewiston that appeared to indicate that he was an orphan.

Joseph Patrick O’Shea did have an association with the Healy Asylum for Boys, an orphanage and boarding school established in Lewiston in 1893 by the Sisters of Charity from Quebec, and he may have been an earlier student in one of the parochial schools established by the Catholic church in Lewiston as early as 1882. The Sisters of Charity, formerly Nursing Sisters, moved with 40 children to a home in Lewiston in 1888 and began to teach in a parish school. In 1893 they established the Healy Asylum for boys. At the time, children in the Healy Asylum for Boys may not have been without parents but were often from families whose parents both worked or, as may be in this case, his mother may have been a single working parent.

Lewiston was the destination for thousands of French-Canadian workers from Quebec in the 1870’s who came to work in the textile mills. The blocks where the workers settled were known as “Little Canada”. Lewiston and Auburn cities had built a railroad spur line to the Montreal-Portland Railway run by the Canadian National Railway that would have facilitated transportation of this very large French-speaking community to Lewiston.

Quebec City was a Jesuit town: the Jesuits there could help him get into the university, but the hard work would be up to him. Joe (as he was affectionately called) studied medicine at Laval University in Quebec City,graduating after eleven years of study. He would work on the railroads a year and then go to university a year! In 1911 he came to Saskatchewan along with two fellow physician classmates. Joe set up practice in Radville and one of these friends, Dr. Parent, set up practice in Sedley. Radville has a large proportion of French-speaking people. It was incorporated in 1911, the year Dr. O’Shea came to this small prairie town. One of the historic buildings in Radville today is the local restaurant. The building started as the Bon Ton Barber Shop and the first doctor in Radville, Dr. Joseph P. O’Shea’s office which later became a restaurant with a series of different owners over the years.

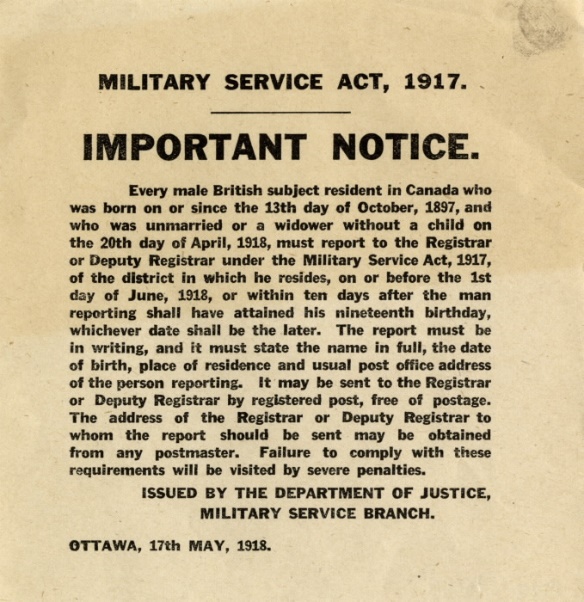

Joe volunteered to serve in the Canadian Expeditionary Force CAMC (Canadian Army Medical Corps) in 1917. He was 37 when he signed up. For the first two years of the war, Canada relied on a voluntary system of military recruitment but in 1917 adopted a policy of conscription, or compulsory service only after a long, difficult political debate. Canada did not have enough recruits to reinforce the Canadian Expeditionary Force, whose numbers were being depleted by the awful toll of the fighting in France and Belgium. The Military Service Act was passed in the House of Commons on July 24, 1917. On August 28 conscription became lawbut call-ups didn’t start until January 1918.

It is not known if the debate over conscription was a factor in Joseph’s decision to enlist, but he enlisted June 26, 1917 and left for England August 13th, 1917. Although the number of conscript soldiers was small compared to the 425,000 Canadians who served overseas throughout the war, conscripts were vital in bolstering the depleted divisions of the Canadian Corps during the final, important battles of 1918. Joe served in the Canadian Army hospitals in England until June 1918 when he was posted to France. For the first three months in France he served in the Number 2 Canadian Hospital, the first Canadian general hospital established in France at Le Treport, a small port on the English Channel.

Given its limited size and experience at the beginning of the war, the Canadian Army Medical Corps performance was truly remarkable. Altogether, 89 % of patients reaching a Canadian hospital survived their injuries. The response of qualified Canadians to the pressing need for medical personnel is also noteworthy. More than half of all Canadian physicians served overseas at some time during the war.

Joe was part of the Canadian Expeditionary Force at a time history records as The Last One-Hundred Days. “The hundred days from August 8, 1918 to the Armistice was Canada’s finest hour. It faced and destroyed the German divisions wholesale successfully, assaulted the enemy positions of great strength and made a huge contribution to the Allied victory. “(from Hells Corner by J.L. Granatstein 2004)

August 17, 1918 Joe transferred to the 1st Canadian Field Ambulance attached to the 1stDivision, 3rd Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force also known as the Queen’s Own Rifles based in Toronto.

Some of the conditions these doctors worked under during that war are recorded in an excerpt from “The Battalion Doctor”:

It is the cold and nervous hour before the attack. The Medical Officer is in a position immediately behind the “jumping off” line. He has organized his staff to cover the battalion front and with his sergeant and corporal burdened with medical supplies, he waits the barrage. As soon as it falls he moves off with the first wave of attack. For him it is not a question of waiting in a dugout to receive the wounded, he must be with the battalion to do the ordinary work of first aid and to establish his dressing station the moment the “objective” is reached. So, he goes into the smoke and tumult of action, to take his chance and, if need be, to give his life to the service of his men.

How many owed their lives to him

No man shall tell;

Into the fiery hell,

over the top in half-light din,

Unsent he went,

Seeking them there,

And to the depths of their despair

The M.O. (medical officer) in action was beloved of every man who saw him in action. An aid post is a grim spectacle. There are rows of stretchers, huddled groups of walking canes, blood everywhere and the sound of suffering in the air but in the midst the doctor at his merciful work, haggard and wan he may be from sleepless nights and unresting days, but he has about him an air of authority, a suggestion of undismayed confidence which, in itself, reassures and comforts weary men. Honor to which honor is due! Be he the battalion doctor or the officer in the field ambulance, or the surgeon in the operating room of the casualty clearing station, or the base hospital, here is a man who through courage and devotion has maintained and advanced the traditions of a professional which from its earliest days, has stood for unselfish service of mankind.

Battles fought by the CEF in the last hundred days stretched across Northern France from Amiens to Valenciennes with their arrival at Mons, Belgium on November 11, 1918. The Canadian Army was a mobile force advancing with each battle won over a distance measured in kilometers whereas previous advances were often measured only in meters. Dr. Joseph O’Shea, while serving with the 3rd Battalion was involved in these strategic battles following his deployment as of mid-August 1918.

The battles were:• The Battle of Amiens, 8 – 11 August 1918:

The Battle of Amiens was the beginning of the end of the German armies. A powerful Allied force, spearheaded by Canadian and Australian troops, nearly broke through the enemy lines on 8 August, pushing the Germans back several kilometers.• The 2nd Battle of Arras, 26 August – 3 September 1918:

By succeeding in destroying the very heart of the German defense system, the Canadians enabled the British 3rd Army to advance eastward at a great pace. The success of the operation had a positive effect all along the western front, presaging an imminent Allied victory.

The battle was actually a complex, two-operation conflict, that of the Scarpe and that of the Drocourt-Quéant Line, both part of the overall Allied strategy which consisted of exhausting the enemy who was already retreating eastward. The Battle of the Scarpe resulted in an Allied advance of no less than eight kilometers, while at Drocourt-Quéant, Allied troops expelled the Germans from one of their vital defense systems, advancing another six kilometers and taking up new positions in front of the next obstacle, the Canal-du-Nord.

General Sir Arthur Currie, in his personal War Diary wrote “One of the war’s greatest triumphs”, referring to the 2nd battle of Arras. The two phases of the Arras operation cost the Canadians nearly 11,000 men. It was during the Battle of the Scarpe that Georges Vanier, the future Governor General of Canada, lost his leg while commanding the 22nd Battalion. General Currie praised the 1st Canadian Division in particular for attacking and capturing the Fresnes-Rouvroy and Drocourt-Quéant Lines, which amounted to a penetration of almost ten kilometers.•

Cambrai is situated in the Nord-Pas de Calais region in northern France. It is surrounded by an elaborate system of canals providing links to the Steele and Scheldt rivers to the northeast and drainage of marshy lands. West of Cambrai lies the Canal-du-Nord, whose construction at the outbreak of war had been left incomplete, a serious obstacle to Allied troops advancing from the west. Cambrai was also an important railway and supply hub for the German army.

The difficult task of capturing these two obstacles was given to the Canadian Corps under the leadership of Lieutenant General Arthur Currie. Currie spent the latter part of September carefully planning the attack. Canadian and British engineers were given expanded resources and manpower and ordered to construct bridges to be used in the attack across the canal, and tramway lines for transporting artillery and other supplies to the battlefield.

The operation began on September 27, 1918, with a hair-raising rush across a dangerously narrow canal passage. It continued with harrowing counterattacks coming from enemy troops concealed in woods, firing from bridgeheads, and lurking around the corners of myriad small village roads. It ended in triumph on October 11, when the Canadians, exhausted after days of unremitting fighting, finally drove the Germans out of their most important remaining distribution canter, Cambrai. It was in Cambrai where Joe suffered exposure to a gas attack that left him with chronic bronchitis thereafter. • The capture of Valenciennes, 1 – 2 November 1918:

:

Though the Germans still clung to the city of Valenciennes and held firm their strong position near Marly, the day for them was a disaster. The Canadian Corps capturedroughly 1,800 enemy soldiers and more than 800 enemy dead were counted in the battle area. Canadian losses numbered 80 killed and some 300 wounded.• Arrival in Mons Belgium:

There is no official record of Dr. Joe’s service following Armistice Day but on November 18th, 1918 Canada, represented by the 1st and 2nd Divisions, accompanied by their own Field Ambulances, became part of the Fourth British Army and began its advance to the Rhine as part of the British Army of Occupation in Germany. The Medical Corps was a support element and took part in the approximately 300-mile march into Germany, with the crossing the Rhine by mid-December. One purpose of the occupation was to give France security against a renewed German attack. The Canadians remained at certain bridgeheads along the Rhine in Germany until early 1919. The official War Historian, Colonel G.W.L. Nicholson writes in “A History of the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps” during their time in Germany:

While there were no battle casualties to attend to, ambulances and clearing stations were kept busy caring for many hundreds of sick and wounded Allied prisoners who were found in various hospitals, many of them in a deplorable condition from lack of proper attention.

Joe’s Canadian Army Service Record lists his return to England as March 15th, 1919. A hospital admission to Shorncliffe Hospital, a Canadian Army Hospital, lists his condition as bronchitis due to a gas attack at Cambrai, France. He was demobilized July 31st,1919 and returned to Canada. Upon discharge his health record states “fit for service in Canada only”, due to his continuing compromised lung condition.

After returning to Canada Joe spent two years at Deer Lodge Hospital in Winnipeg, Manitoba. This hospital was a convalescent hospital established in 1916 for soldiers returning from the war. Following his time in Winnipeg he returned to Saskatchewan which may have been the time he met his future wife Bridgetta. He had set up his medical practice in Norquay by the time of their marriage in 1922 where he owned a drugstore with living quarters above. His marriage to Bridgetta Connaughty took place in St. Augustine Church, Wilcox Saskatchewan and was reported in the Wilcox Times as having taken place Monday, April 27, 1922.

Sacrifice

They hearkened to the call and thus

They found themselves amidst a rush

Of bursting shrapnel and of shell

A veritable roaring Hell

Then fell that Liberty might live

Heroes who did sincerely give

All that they loved and lived to call

Mother, Sister, Sweetheart, Wife all

And dying what a sacrifice!

Two deaths in one and dying twice

Killed down the iron crown of might

Giving to each man a freeman’s right

They who into their graves were thrust

Still live – their tombs can hold but dust

– Joseph P. O’Shea, 1921

Some of Joe’s Poems on his prescription pad

Thanks to Sharon Connaughty for the work on this post.

I loved!!! Wonderful memories!!!

So glad to hear from you. Thanks for the picture. You are looking great.

Well done Maureen,

Thanks Rita